A Compleat History of the Magic: the Gathering Metagame, part 24: 2007 Worlds, Lorwyn, and the birth of midrange

Ah, Lorwyn. At the time (and probably still), it was the worst-selling large set in Magic's history. But with the benefit of hindsight, it casts one of the longest shadows of any set of that era. So many original Lorwyn cards would become major competitive staples in constructed formats like Modern, Legacy, or Extended.

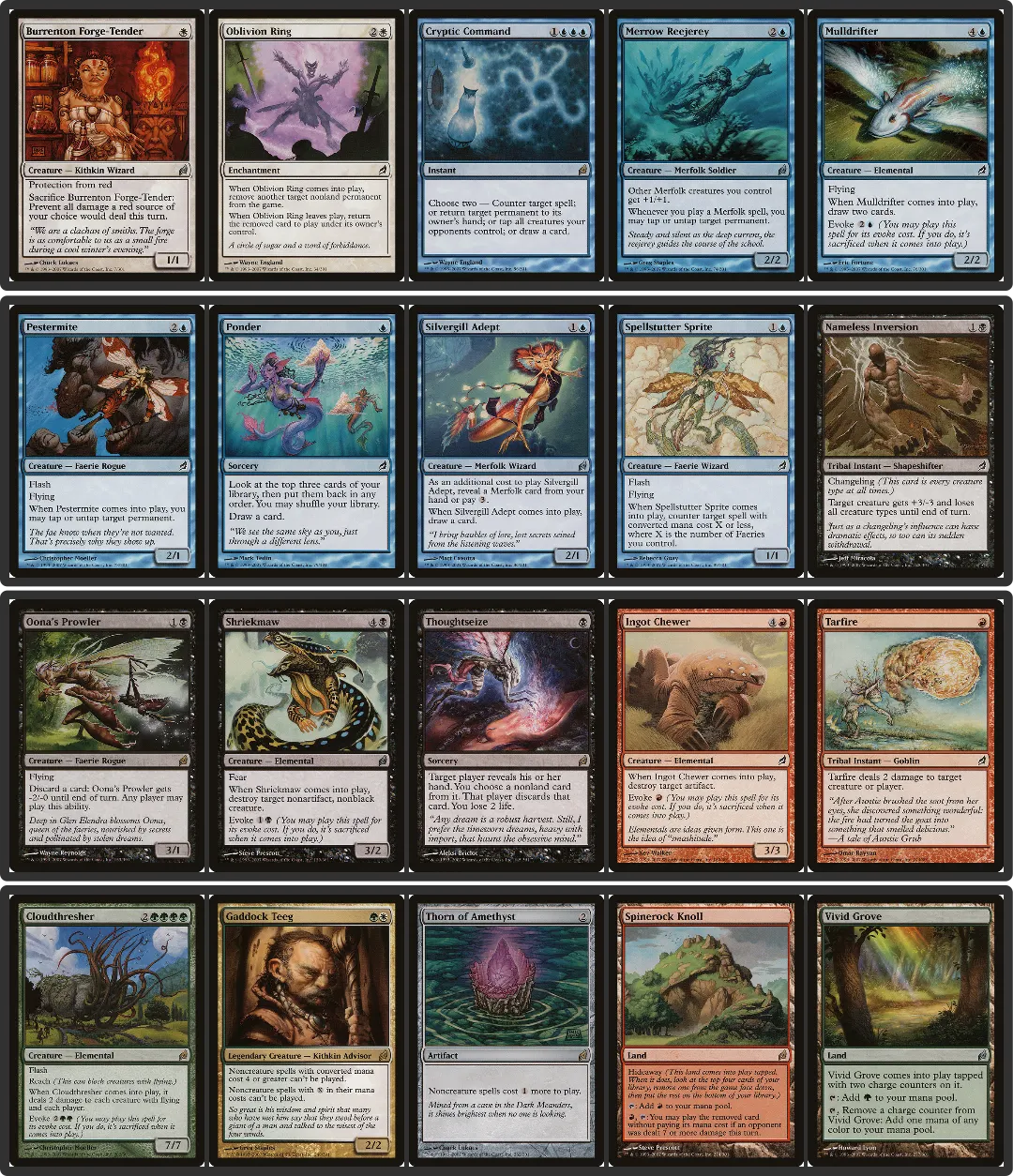

A selection of Lorwyn cards that would be Constructed relevant in various formats for years to come.

Lorwyn's poor sales are probably only partially its own fault. It came on the heels of Time Spiral, a set often credited with driving casual players away from the game with its huge volume of complex cards and different named mechanics. It also had its own share of overcomplicated board interaction, in Limited play especially, which probably contributed. Coming out in October of 2007 might also have something to do with it – maybe Magic set sales are a leading recession indicator.

Ultimately, competitive play makes up a small proportion of overall Magic, and so Lorwyn's design success on that front couldn't save it commercially. But it really is a success; Lorwyn is chock full of impactful cards that are good, but not broken. It touched pretty much every format.

Land, thoughtseize you

Probably no Lorwyn card has more of a far-reaching impact than Thoughtseize. It's been a staple in every single Constructed format where it's legal, but it's never been banned. Duress had existed for years at that point; but then and since, it's always floated between maindecks and sideboards, never quite a defining presence in the metagame.

The thing about a card like Duress is that when you cast it, you spend mana and a card, while your opponent does nothing but loses a card; the card puts you naturally behind. For it to be good, you need to be taking not just a card, not just a good card, not just the best card in their hand. You need to be taking a card that is so important that your opponent's hand falls apart without it.

It needs that high ceiling to make up for its abysmal floor. Targeted discard like this tends to be a bad draw later in the game when both players are topdecking. Even if you have it in your opening hand, Duress can miss entirely; plenty of decks will keep hands with only lands and creatures.

As such, Duress ends up being played in two contexts. It's played against combo decks, where it can take away a crucial piece and hopefully shut down their combo. And it's played by combo decks against control, where it can both take a crucial piece of interaction and give the combo player information on how to proceed.

Meanwhile, Duress' little brother, Ostracize, has never seen meaningful play. Creature cards in creature decks tend to be much more fungible; there's just not nearly as much of an advantage in taking away a creature. Even if you know your opponent is playing creatures, you basically never want Ostracize as opposed to a removal spell that can answer a creature already on the field.

It's interesting, then, that Thoughtseize is so much more powerful than Duress even though the delta between the two is the option to ostracize a creature. Taking your opponent's replaceable two-mana creature isn't great value for your Thoughtseize, but it massively raises the card's floor. It's basically impossible to miss on a turn-1 Thoughtseize1 in the way that you can miss with Duress, and that's enough.

It's so much enough that Thoughtseize's 'lose 2 life' clause seems kind of laughable. Historically, people have never been cagey about jamming four Thoughtseizes into their deck no matter how aggressive a format is, which really says something about the putative value of two life. Future iterations of this targeted discard archetype will never hit the power level of Thoughtseize. Only Inquisition of Kozilek will come close, emphasizing the importance of almost never missing.

Thoughtseize is going to be massively important in enabling several of the archetypes that make Lorwyn-era Standard what it is, and into the future. I've talked previously about tempo decks; decks that plan to play a cheap early threat and then use interaction to keep the opponent from dealing with that threat or progressing their own game plan.

Thoughtseize enables a similar play pattern, but it flips the script. You take away the opponent's ability to react or press their own game plan pre-emptively, and follow up with a bigger threat. Thoughtseize is an all-format, all-archetype all-star; it'll get played in all kinds of decks. But right now, in late 2007, it's going to help usher in the birth of the archetype that will define most – not all, but most – Standards going forward: midrange.

Doran the Exploran

Uri Peleg won Worlds 2007 with this then-unusual list; he called it 'BGw aggro', but I think most modern players would call this an archetypal midrange list; as always, I'm using a modern naming convention.

Black-green midrange decks were all over the field at that tournament, and they certainly beat up on other aggro strategies people were trying. These decks exemplify what would become the classic play pattern for midrange: spend your early turns preparing and/or disrupting your opponent, then hit them with a big, hard-to-answer threat.

At the time, this type of black-green deck was known as 'rock'. The origins of this nickname probably go back to old Deranged Hermit decks; the card may have been known as 'the Rock and his millions', which I understand is a wrestling reference. But the name probably stuck because of what the archetype represented: a grindy, tough deck that had a ton of staying power.

What set these decks apart from a classic aggro deck is their access to various sources of on-board card advantage. Garruk Wildspeaker is probably the biggest one of those, and the most impactful of the Lorwyn planeswalkers; he comes down, makes a 3/3, and then continues to make 3/3s, make mana, or threaten to Overrun the opponent. But besides the planeswalkers, these decks are also playing creatures like Masked Admirers and Shriekmaw.

This reflects a shift in how Magic is being designed. Card advantage used to be almost the exclusive province of blue; cards did one thing, and card drawing was how you got more cards. But around this time, Magic design was pivoting around a couple of core ideas:

- Creatures are inherently the most important element of the game, and so the game should have good creatures that are worth playing competitively

- Creatures that cost more than 2 mana are popular and have a lot of cool design space, but they mostly interact poorly with removal spells that tend to cost 2 mana.

- If a creature does something merely by coming into play, now it interacts well with removal.

Creatures that do something when they enter play are nothing new, of course; Nekrataal was originally printed in Visions. But this type of design was becoming more prevalent, and more of the Constructed viable cards fell into the archetype of 'value creatures'. Lorwyn in particular had a whole mechanic, Evoke, which exclusively goes on value creatures; many were Constructed relevant, including Shriekmaw.

Thus, a new class of deck was emerging to take advantage of this new card archetype. These decks weren't aggro decks trying to turn their hand into damage as fast as possible; but neither were they control decks built to hold the game in suspension indefinitely. These decks were trying to use disruption, mana acceleration, or smaller threats as a bridge to get to those 4 and 5 mana plays.

These decks would come to be known as 'midrange', though the term wasn't in widespread usage at the time yet. Not quite aggro, not quite control; something in between.

Once they have access to 4 or 5 mana, they are just trying to 2-for-1 the opponent every turn until they win. These sources of card advantage allow midrange decks to grind out games; even if they don't quite get the kill by curving out, their late-game topdecks are much better.

But a huge part of their advantage comes against aggro; these decks go 'over the top' of aggressive decks, matching aggro's creatures with bigger creatures, efficient interaction, and eventually card advantage.

Peleg's insight was seeing how good the BG decks were going to be and building his deck to beat not only all the decks they beat, but the standard BG decks themselves. Hence, Doran the Siege Tower. For the most part, it's played in the deck just as a (de facto) 5/5 for 3 mana, a really good rate in those days; the challenging casting cost is smoothed over with, among other things, four copies of Birds of Paradise.

In this tournament, Doran is a classic example of a card that's amazingly well positioned; it's powerful in context, more so than inherently. It doesn't die to most of the black removal. It can block Shriekmaw. It's bigger than all creatures other than the biggest Tarmogoyfs; and when a Doran is in play, Tarmogoyfs trade rather than bouncing off each other - which can clear a path for Doran himself. It even turns your Birds of Paradise into a valid attacker in the air.

What grows the Tarmogoyf

This was the first Pro Tour-level Standard event where Tarmogoyf was legal, so it's as good a time as any to talk about Tarmogoyf's role in that format; here, it mostly appears in black-green decks Peleg was playing – though it's not the first competitive Tarmogoyf deck overall.

These decks used Tarmogoyf both as a two-mana play that bridged the gap between the early interaction and the later value plays, and as a two-mana card that was still worthwhile if drawn late in the game. It did well in that role, but the card really wouldn't achieve its status as one of the most format-defining creatures ever in Standard; its power scales with the format, and it was much more impactful in Modern and Legacy.

Tarmogoyf is a deceptively nuanced card. There's really two Tarmogoyfs, which I'll call the 'fair' Goyf and the 'eternal' Goyf.

The 'fair' Goyf is the way the card is mostly played in Standard: It's a two-mana play whose size tracks the progression of the game. This means that it's a much better late-game topdeck than most two-mana creatures, and it tends to become more and more relevant as it sits on the board, but it's not really an 'oversized threat' as such. The best case for 'fair' Tarmogoyfs is that you cast Thoughtseize on turn 1, take a non-sorcery out of your opponent's hand, and your turn-2 Tarmogoyf is a 2/3. Totally fine for the era, but nothing special in a world of Wren's Run Vanquisher.

If you were truly cooking, maybe you took a planeswalker with your Thoughtseize and then killed your opponent's creature with Eyeblight's Ending, giving you a 5/62 Tarmogoyf attacking on turn 3; but that requires things to line up just so in a way that wouldn't happen most games. Here's a different sample hand from the Peleg deck: Tarmogoyf, Shriekmaw, Doran, Garruk, lands. Totally keepable and fine hand, but it won't do much to grow the Tarmogoyf.

'Eternal' Goyf is almost a totally different creature. I won't go into detail about the Tarmogoyf decks in Modern and Legacy, but suffice to say that those decks played fetchlands, a lot of one-mana instants or sorceries, and sometimes even cards like Mishra's Bauble. Tarmogoyf, as a card, scales really well to a format being faster or more efficient.

Weathering the storm

It's impossible to talk about this tournament without talking about what was almost the most successful rogue deck in Magic history; the deck that almost dominated the tournament completely. That was Patrick Chapin and Gabriel Nassif's new version of Dragonstorm.

Unlike the blue-red storm we talked about last time, this version was a mono-red deck that hybridized Storm with a burn deck employing Pyromancer's Swath and a bunch of direct-damage spells. The two strategies neatly overlapped around Spinerock Knoll.

This deck played almost like a combo-control deck; the overall strategy was to spend the first few turns suspending Lotus Blooms and Rift Bolts, banking mana into Molten Slagheap, and maybe using cheap burn spells to control the game by killing a creature here and there.

Then, eventually, the storm player would use all their fast mana to play Pyromancer's Swath and hit the opponent with multiple powered-up burn spells. It only takes two burn spells to unlock the Spinerock Knoll, which would typically hide a Storm spell or a Bogardan Hellkite to finish the opponent off.

Swath's interaction with Grapeshot turned that spell from one of the most demanding Storm kills to one of the easiest, since it's counted for each individual copy over and over again. With Swath in play, 7 copies of Grapeshot equals 21 damage; this meant that the deck needed a lot fewer cards and a lot less mana for its combo kills than a typical storm deck.

It also gave the deck outs to win without a single explosive turn; Lotus Bloom into Dragonstorm is already a very powerful play that would often be enough to win the game. All of this added up to a deck that was very powerful and hard to stop; Chapin thought the field would be unprepared for combo, and he was right.

This deck is probably one of the last times that a deck really came out of nowhere to take a major tournament like this. Magic Online was fully functional at this point and the metagame would only become more closely scrutinized and faster-moving. But in 2007, it was still possible for Chapin and his group – which included legends of the game like John Finkel and Bob Maher – to be basically the only ones who knew about the deck at the tournament, collecting a huge advantage. All but one of the players who brought it finished day 1 at 4-1 or better.

Of course, it's worth emphasizing that the players in question were legends of the game. This deck was probably one of the most technical Standard decks of all time. It's the ultimate test on knowing when to use your burn spells on your opponent's face versus when to use them on their creatures. As a Storm deck without much in the way of traditional card advantage, playing around the severe drawback on Pyromancer's Swath, the deck operates on a razor thin margin and evaluating these small decisions is huge.

Ultimately, though, Chapin and Nassif didn't win the tournament; Peleg did, with his Doran version of green-black. What's impressive about the storm deck is that while it was extremely powerful and a huge surprise, it wasn't actually well positioned. Chapin himself openly knew that he was disfavored against the black decks; here we see an early example of Thoughtseize being a strong maindeck card that also has a lot of upside in specific matchups.

Without access to real card draw (other than two copies of Wheel of Fate in the sideboard), Chapin's deck really needs all its cards to win, and a Thoughtseize could be devastating. Even with this disadvantage, he managed to navigate a lot of tough matches to make it to the finals against Peleg. But he couldn't get over that final hurdle against Peleg's mix of disruption, pressure, and smart sideboard choices like Stupor.

Next time

The notable thing about this early Lorwyn metagame is that it pretty much evaporated in a matter of months. Both Swath-based storm decks and Doran would soon be overshadowed by cards that came out in Eventide.

Lorwyn block had a unique (at the time) structure. For years, Magic design had struggled with the block structure. Each year of Magic was made up of one large set followed by two small sets. Those two small sets would follow up the large set, mechanically and thematically. Often, the themes that put in place in the first large set of a block would be basically mined out by the time the small sets came around. Small sets tended to be, among other flaws, underpowered.

Wizards is going to spend years trying to solve this issue before giving up and abolishing small sets altogether. I've already talked about some of the early attempts with Coldsnap, but Lorwyn block marks a major turning point.

Lorwyn would be followed by the single small set Morningtide. Those two sets would be drafted together, but there was no third small set. Instead, the large set Shadowmoor and its small set Eventide would follow that. Shadowmoor and Eventide take place on the same world (sort of), but they have totally distinct mechanical themes; the plane of Shadowmoor is actually Lorwyn's shadow version, the night-time scary story to Lorwyn's sunlit fairytale.

Morningtide by itself was going to completely reinvent the Standard metagame. It's not nearly as impactful, long-term, as Lorwyn; but it still had a few cards that would enable whole new archetypes.

Next chapter: we meet midrange's evil twin.

Okay, historically there have been decks that will keep all-land hands, and there is such a thing as 'six lands and Obstinate Baloth'. But those are very rare outliers.↩

Eyeblight's Ending is a Kindred card, then known by the now-deprecated term 'Tribal'. Kindred is its own card type, so it counts as two things for Tarmogoyf, giving a graveyard containing sorcery, planeswalker, instant, kindred, and creature.↩